Black Mirror‘s latest cautionary tale concerns an interactive book within an interactive game within an interactive meta-narrative.

I’m a cautious fan of Netflix’s dystopian tech anthology Black Mirror – I’ve seen all the episodes, and when they’re good, they’re fantastic. Of course, they’re not always good.

A few days before New Year’s, Netflix stealthily released Bandersnatch, a one-off Black Mirror episode with a catch – an interactive storyline, which is a first, both technically and creatively, for the platform. The early reviews I read were lukewarm, diminishing my curiosity, but I eventually got around to watching Bandersnatch. Here’s where the story took me… or rather, where I took the story.

Very, very mild spoilers below….

I’d read that many devices didn’t support the interactive navigation, so I was surprised and pleased that the Netflix app on my Samsung TV was up to speed for this. The episode begins much like any other, setting up the story of Stefan, a young, ambitious computer game developer in 1984, living at home with his father. A few minutes into his morning, his father asks him which cereal he’d prefer – Sugar Puffs or Frosties?

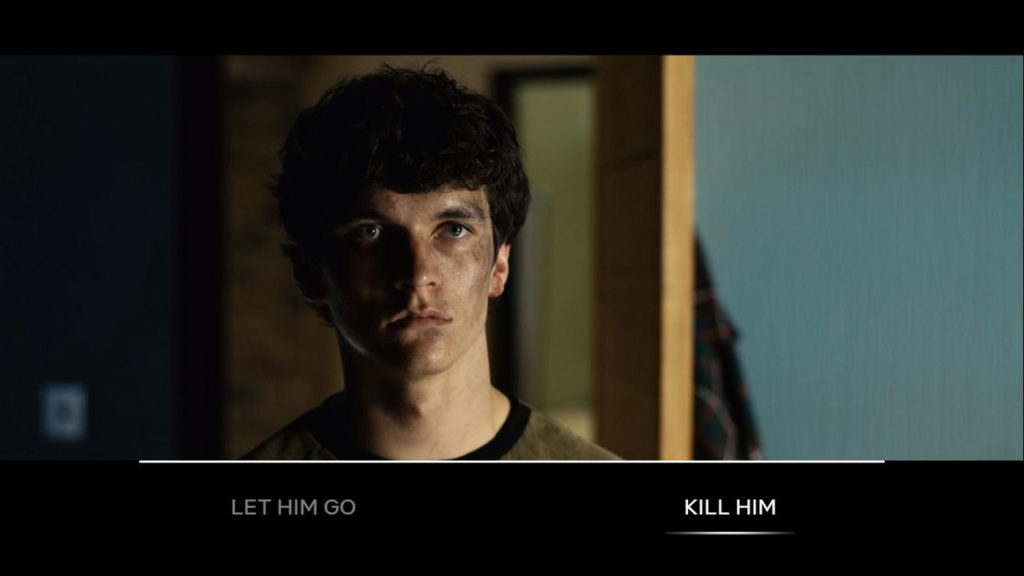

This triggers our first interactive choice. Below the widescreen content, the two choices appear, one to the left and the other to the right. A white stripe contracts slowly toward the middle of the interface, indicating our limited decision time. The video doesn’t pause here – it keeps going, as we witness the protagonist’s thought process. Using the arrows on my remote control, I was able to simply select between the left or right options. Once you’ve made a selection, there’s no changing your mind, even if time still remains.

When the timer elapsed, the video continued seamlessly, without a definitive edit point, and the character opted for Frosties just as I had. The narrative continued as if the choice hadn’t mattered – and ultimately, while the cereal choice shows up again quite a bit deeper into the story, it didn’t make a difference in the plot’s outcome. This was a superficial choice, but as such, it was a good introduction to the navigation mechanic. The options would become more intense soon enough.

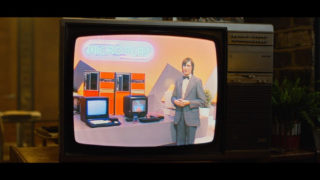

We learn a little backstory in this opening scene – Stefan has an important meeting with Tuckersoft, an up-and-coming computer gaming company, and he’s been developing Bandersnatch, a game based on a ‘Choose Your Own Adventure’ book that had belonged to his late mother. On his way to the meeting, Stefan makes his next choice – should he listen to a Thompson Twins cassette, or a ‘Now!’ compilation? We get to hear the results (in the latter case, it’s a track by Eurythmics). Again, the choice is superficial, and again, it will be referenced later on.

It’s at the gaming office where the plot – and interactivity – kick into action. Stefan meets the company’s owner as well as his idol, a hotshot game designer named Colin. He shows off his game-in-progress – it crashes, but he’s still offered a job. Does he want to work in the office, or keep developing the game at home?

I made a choice here that resulted in my story coming to an end about 30 seconds later. But instead of starting from scratch, I was given a quick-cut montage of the preceding events and landed back at the game company to repeat the previous scene. Only this time, things were different. Characters seemed to have a trace memory of what had just occurred, while simultaneously being confused at how they came to know this. This time, when I chose the other option, Stefan seemed resistant… like he really preferred my initial choice.

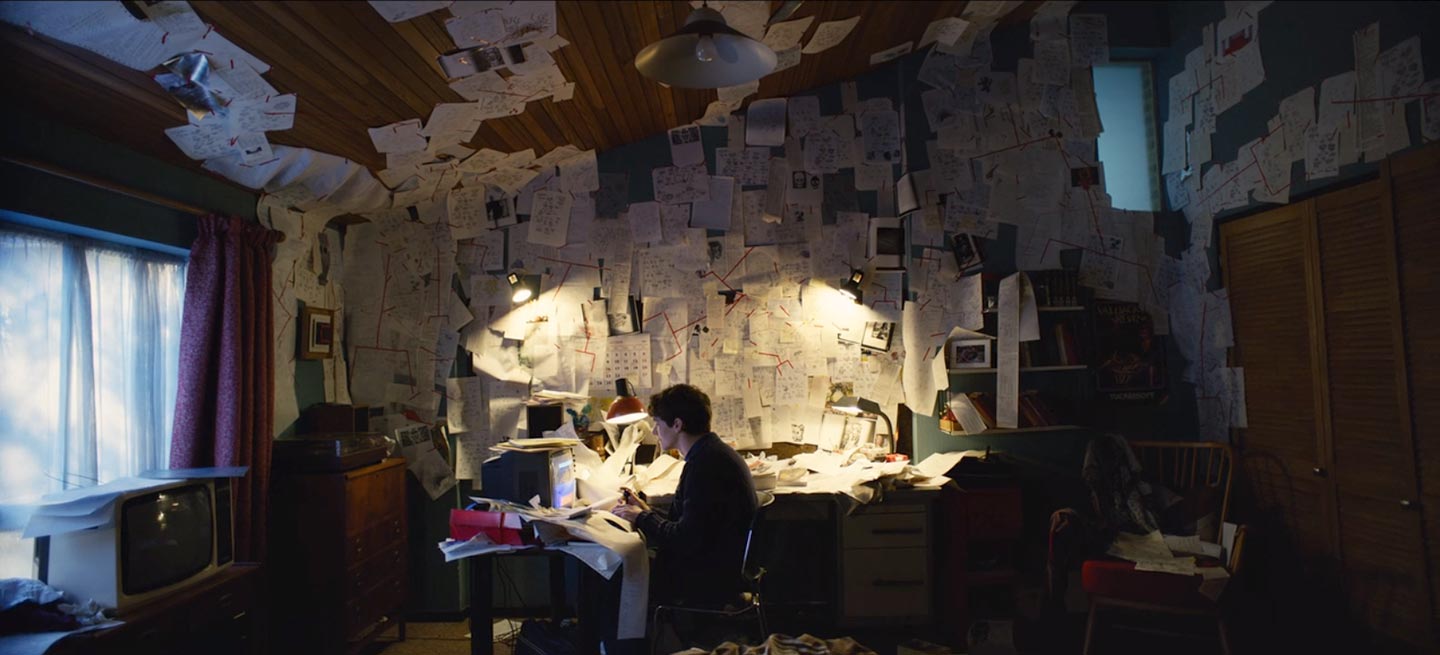

Here’s where the concept behind Bandersnatch really revealed itself to me – it’s a story about a ‘Choose Your Own Adventure’ game, structured as a ‘Choose Your Own Adventure’ game, where the characters become aware of their predicament. It’s all very Black Mirror, though surprising, and at times, the cleverness and absurdity of the meta-narrative made me laugh out loud.

But it wouldn’t be Black Mirror without darkness. Depending on the path chosen, Stefan may end up alive or dead, sane or insane, a victim or a killer. There are action sequences, conspiracy theories, monsters, and hallucinatory drug trips. Each time through, the story concludes with a clip of a critic reviewing the titular game. My first go-round got me zero stars out of five, in what may be the happiest, if least exciting, of the ending choices.

Bandersnatch typically let me try again after each game ending, often giving me a choice of where to pick up the story – after about 90 minutes, I finally got forced into the end credits. In this time I’d caught about 4 endings, and about half of the broader plot paths. User-made maps of the story can be found on the Internet, but even these didn’t catch all the complexity; Netflix recently tweeted a clue to an ending that hadn’t yet been widely reported. A second viewing, aided by the story maps, let me to some of the more extreme storylines, including the gruesome ‘five star’ ending.

I thoroughly enjoyed watching (playing?) Bandersnatch. It’s well-acted, and beautifully made, with some enjoyable 80s references. The meta-narrative kept me thoroughly entertained, especially when a 21st century streaming media firm intruded anachronistically into the narrative. As dark as the storylines can get, they’re forgiving… you can always try again with the hope for a better outcome. There’s even one melancholy ending that elegantly provides closure to the story’s central familial conflict.

Bandersnatch is ultimately ‘about’ its interactivity, and the sum total of its outcomes. There’s no ‘correct,’ or ‘winning’ ending – just as there’s never only a single ending. As one character states moments before dying, “See you in the next life.”

So, can Netflix and Black Mirror do it again? The complexity of Bandersnatch, with over four hours of footage, has been blamed for delaying the entire fifth season of Black Mirror. It wasn’t easy, or inexpensive, to plot, produce, or engineer. But in the struggle, its creators figured out a way to make interactive TV technologically feasible and intuitive for viewers.

The challenge, I think, lies in whether content-creators can invent stories that are robust and entertaining enough to be carried into multiple directions without losing their core. Bandersnatch‘s meta-narratives make it a perfect match for the interactive format, and set the bar high for what’s next to come.