If a digital interactive goes untapped in a forest… someone is still there to see it.

One of the first unfamiliar phrases I encountered when I began working in multimedia exhibits was “Attract Loop” – the animation that appears on a digital screen when it’s not in use. It’s a term that I still avoid using with clients, as it’s both confusing and a bit crude. Still, I’ve spent more than two decades now wrestling with the notion of attract loops – what they should or shouldn’t be, and why we need them.

Little has been written about attract loops (as little has been written about environmental media!), so in this post I’m going to try to lay out a basic taxonomy of the form, based on my own experiences as well as recent observations.

Note: the following examples make specific reference to touch interaction, but many of these methods will work just as well for experiences initiated through physical interfaces, RFID check-ins, or gestures.

The Prompter

This is the basic attract loop. The title identifies the interactive; there may be a subtitle explaining it in a little more detail, or a prompting question, but generally that’s about it. It may have some ambient animation, or a ‘build’ of the title text… and since there’s nowhere to go from there, the text will typically hang around for a moment, and then disappear to build itself again.

This is the basic attract loop. The title identifies the interactive; there may be a subtitle explaining it in a little more detail, or a prompting question, but generally that’s about it. It may have some ambient animation, or a ‘build’ of the title text… and since there’s nowhere to go from there, the text will typically hang around for a moment, and then disappear to build itself again.

This approach assumes that visitors already a) understand what the interactive is, and b) have a keen interest in using it. If that’s not the case, it can seem a little bit lazy.

The Navigator

The Navigator cuts to the chase, presenting a menu of immediately selectable options. The visitor’s first interaction here is in fact making a navigation choice. This can work when the content of the piece is immediately apparent; for example, a grid of video stills might lead to the media iteself, or a gallery map might provide information about different artworks. In both these cases, the content is pretty much what the visitor expects. There’s not much ‘experience’ to the experience; it’s functional and immediate.

The Navigator cuts to the chase, presenting a menu of immediately selectable options. The visitor’s first interaction here is in fact making a navigation choice. This can work when the content of the piece is immediately apparent; for example, a grid of video stills might lead to the media iteself, or a gallery map might provide information about different artworks. In both these cases, the content is pretty much what the visitor expects. There’s not much ‘experience’ to the experience; it’s functional and immediate.

The Contributor

This is the inverse of a typical attract loop, as its primary content appear when it’s not in use, and visitors can interrupt the flow to make adjustments. It’s the ‘un’-attract.

This type is often seen for user-generated content experiences – where data visualizations or visitor-designed artworks may appear in sequence without interaction. Visitors can jump in to share an opinion or create something, thereby altering the attract loop. The biggest challenge with this type of content-heavy attract loop is that visitors might not perceive that interaction is an option.

The Curator

The Curator aims to give visitors a preview of the content they’ll see once they interact. This is most common, naturally, when the exhibit is primarily a means of presenting detailed content that’s not available elsewhere in the gallery.

The Curator aims to give visitors a preview of the content they’ll see once they interact. This is most common, naturally, when the exhibit is primarily a means of presenting detailed content that’s not available elsewhere in the gallery.

These loops often include creative animation – sometimes more cinematic than what visitors will encounter once they begin the application. They work best when content is king – when it’s compelling enough that visitors will reach out to explore more.

In a gallery filled with dozens or hundreds of objects, though, they may have to work harder to overcome visitor fatigue, and show that there’s something more worth exploring.

The Player

The Player is the converse of the Curator; rather than focusing on content, this model advertises the interaction itself. It’s most commonly seen with exhibit games or play-based activities, where the attract loop shows a preview of the game in action; the colorful graphics and animation that comprise the interaction can be the best enticement to participate. Sometimes it can be a little confusing to visitors, as it can look like the game is ‘playing itself,’ so it may be necessary for text to clarify that this is something visitors can ‘do’ rather than simply watch.

The Player is the converse of the Curator; rather than focusing on content, this model advertises the interaction itself. It’s most commonly seen with exhibit games or play-based activities, where the attract loop shows a preview of the game in action; the colorful graphics and animation that comprise the interaction can be the best enticement to participate. Sometimes it can be a little confusing to visitors, as it can look like the game is ‘playing itself,’ so it may be necessary for text to clarify that this is something visitors can ‘do’ rather than simply watch.

The Tutor

The Tutor is similar to the Player, but more visitor-centric; here, we may see actual images of visitors interacting, as a way of not only demonstrating the nature of the activity, but providing a quick tutorial. Videos of visitor interaction are rare in these cases; more likely, an animation will show the interaction step-by-step, sometimes with animated hands to indicate where visitors might tap the screen. Where the Player shows you what will happen, the Tutor shows you how you yourself will make it happen.

The Tutor is similar to the Player, but more visitor-centric; here, we may see actual images of visitors interacting, as a way of not only demonstrating the nature of the activity, but providing a quick tutorial. Videos of visitor interaction are rare in these cases; more likely, an animation will show the interaction step-by-step, sometimes with animated hands to indicate where visitors might tap the screen. Where the Player shows you what will happen, the Tutor shows you how you yourself will make it happen.

The Marketer

The Marketer is a video or animated presentation that incorporates content and messaging, and may be entertaining or informative in and of itself.

The Marketer is a video or animated presentation that incorporates content and messaging, and may be entertaining or informative in and of itself.

This type is most common in branded environments, where there can be a lot of messages to be pushed, and branding teams may want to utilize existing media assets. I’ve developed – and argued for – quite a few of these in my time, with the rationale that the digital displays could function as signage and promotion when not in use as interactives.

But I’ve found that this can undercut the experience in a number of ways. If the display is presenting a steady stream of product information, visitors often don’t realize that there’s interaction to be had… and if they do realize this, there’s little motivation to interact, since they’ve already seen the content.

Composite Types

It’s quite common to see combinations of the above styles – for example, loops that alternate between an Marketer branding sequence and a Player interaction preview.

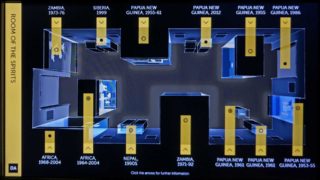

For multi-screen experiences, it’s often the case that only one interface is used for interaction, while other displays simply present media. In these cases, the Prompter title screen my make sense for the interaction zone, since the more prominent displays may function in an ongoing Curator or Player style.

For multi-screen experiences, it’s often the case that only one interface is used for interaction, while other displays simply present media. In these cases, the Prompter title screen my make sense for the interaction zone, since the more prominent displays may function in an ongoing Curator or Player style.

On the other hand, with a single large display and multiple users interacting, things become a bit more complicated. A typical attract loop will disappear once the first visitor begins to interact. In this circumstance, it’s often useful to have additional secondary prompts, letting visitors know that they can still join in, even though another guest has begun using the experience.

I’m sure I’ve missed a few permutations of the classic attract loop. But are they even necessary? Next time I’ll examine the question of why we ever needed attract loops in the first place….

One thought on “Rules of Attract Loops, Part 1”

Comments are closed.